"...figuring out how much oil lies beneath the water's surface—something satellites can't show..'It's not a matter of predicting if it's going to be there or not,' Roffer said. "It's there.".

"Researchers...have discovered what initial tests show to be a wide area with elevated levels of dissolved hydrocarbons throughout the water column..'Our concern regarding these contaminants is they have the potential to be incorporated in the food web,' said David Hollander, a chemical oceanographer who is a lead investigator in the research mission.""

http://news.nationalgeographic.com.au/news/2010/05/100518-gulf-mexico-oil-spill-loop-current-science-environment/

Gulf Oil Is in the Loop Current, Experts Say

Satellite pictures show oil snared by an eddy.

Christine Dell'Amore

National Geographic News

Published May 18, 2010

Part of an ongoing series on the environmental impacts of the Gulf oil spill.Some oil from the Gulf of Mexico spill is "increasingly likely" to be dragged into a strong current that hugs Florida's coasts, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) officials said today.

But other experts say that the oil is already there—satellite images show oil caught up in one of the eddies, or powerful whorls, attached to the Loop Current, a high-speed stream that pulses north into the Gulf of Mexico and travels in a clockwise pattern toward Florida.

Images from the past few days show a "big, wide tongue" of oil reaching south from the main area of the spill, off the coast of Louisiana, said Nan Walker, director of Louisiana State University's Earth Scan Laboratory, in the School of the Coast and Environment.

Meanwhile, a particular eddy has intensified and expanded north in recent days. The images reveal that the eddy has snagged oil and pulled it southeastward 100 miles (about 160 kilometers), which means the crude is now circulating inside the turbulent waters.

The oil has also reached the point where the eddy connects to the Loop Current, Walker said. That means the oil is traveling eastward alongside the main stream of the Loop Current, and it's likely that it will continue flowing with the current to Florida, Walker said.

Mitchell Roffer, president of Roffer's Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service in West Melbourne, Florida, has also been tracking the oil spill by satellite.

"Several scientists from different organizations have seen the oil in the Loop Current" via "clear and dramatic" satellite pictures, Roffer said.

"Nowhere to Go But On the Beach"

According to Roffer, the northeast portion of the Loop Current has been moving eastward, closer to Tampa, on Florida's western coast (map). That means if an eddy sweeps the oil into the main current, it has "nowhere to go but on the beach," Roffer said.

Once in the Loop Current, oil can travel south and enter the Gulf Stream, a powerful ocean conveyor belt that carries warm water up the eastern seaboard.

Oil brought to Florida's east coast could then get pulled into inlets and harbors, where it would settle into the mangrove forests that are nurseries for many species of sea life, Roffer pointed out in early May. (See pictures of ten oil-threatened animals.)

On Monday the Coast Guard reported the discovery of 20 tar balls at Key West's Fort Zachary Taylor State Park. The sticky balls of congealed oil are currently being analyzed to determine if they came from the Gulf spill. (See pictures of tar balls and dead dolphins that washed up on Alabama beaches.)

But Roffer said it's unlikely that oil-contaminated Loop Current waters could have reached Key West in that short amount of time.

The current travels about 50 to 100 miles (80 to 160 kilometers) a day, so it would take roughly 13 days or more for oil to get from the site of the damaged Deepwater Horizon rig to Key West, LSU's Walker said.

Oil Lies Beneath?

Researchers from the University of South Florida will venture into the Loop Current via boats later this week to collect water samples and verify the oil's presence, according to the Associated Press.

Such testing is "absolutely" necessary, Roffer said, as is figuring out how much oil lies beneath the water's surface—something satellites can't show.

What the satellite pictures definitely reveal, he said, is that the time for modeling whether oil might get into the Loop Current is over.

"It's not a matter of predicting if it's going to be there or not," Roffer said. "It's there."

Invisible Oil Detected in Gulf

http://usfweb3.usf.edu/absolutenm/templates/?a=2362&z=31

USF’s R/V Weatherbird II Detects Invisible Hydrocarbons in Gulf Waters

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DuKZEPmULs0&feature=player_embedded

By Vickie Chachere

St. Petersburg, Fla. (May 28, 2010) – Researchers aboard the University of South Florida’s R/V Weatherbird II conducting experiments in a previously unexplored region of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill have discovered what initial tests show to be a wide area with elevated levels of dissolved hydrocarbons throughout the water column, possibly indicating that a limb of an undersea oil plume has spread northeast toward the continental shelf.

(A June 7, 2010 report by CNN.com covers the findings of USF scientists and researchers. Click here to view the report.)

The Weatherbird II deployed a variety of instruments to detect the signature of hydrocarbons, which will undergo further testing to verify if it Deepwater Horizon oil. The probable concentration of dissolved hydrocarbons was highest at 400 meters below the surface.

"The ramification is that what we see at the surface is not the entire story," said Ernst Peebles, a biological oceanographer who was aboard the Weatherbird II and is one of the lead researchers on the project.

"This is not a big glob of oil drifting," he said. "These are layers. They show up on sonar as layers with clear water in between."

The discovery is significant because it verifies the presence of dissolved hydrocarbons in the deep recesses of the Gulf of Mexico that cannot be seen with the human eye but could eventually become a threat to marine life and habitats.

Samples and data gathered during the voyage are now undergoing additional testing. Given the "insidious" nature of dissolved hydrocarbons on marine environments, the discovery has scientists concerned.

The R/V Weatherbird II made its discovery on Tuesday afternoon while performing tests along a series of stations east and northeast of the collapsed Deepwater Horizon rig. The researchers returned to the area on Wednesday and performed a precise repeat of their experiments which produced the same results.

The researchers’ preliminary findings came from water sampling using three separate technologies: a CDOM Fluorometer, the ship’s sonar and gliders which are able to assess water conditions as they move through the water column.

“Our concern regarding these contaminants is they have the potential to be incorporated in the food web,” said David Hollander, a chemical oceanographer who is a lead investigator in the research mission.

“The first ecological impact of this spill is the effect on coastal habitats, including marshes, beaches and estuaries. The second threat to nature would be the impact on the food webs. That is what’s at risk.”

The R/V Weatherbird II’s journey in the gulf did have some bright findings for the state of Florida. Several stations where water testing was completed between the Loop Current and the Florida coast showed currently clean water, no weathered oil on the surface and no record of dissolved hydrocarbons at depth.

The researchers were investigating the area northeast of the leaking well after models created by USF’s Ocean Circulation Group Director Robert H. Weisberg indicated that oil plume from the spill might have spread underwater in that direction.

The underwater discovery of dissolved hydrocarbons came in area that is 35 kilometers northeast of the ruptured wellhead and in an area roughly south of Mobile, Alabama.

Scientists will need to conduct further tests to determine whether the suspected dissolved hydrocarbons were caused by dispersants or the emulsification of the oil as it moved through the water away from the leaking well.

The R/V Weatherbird II departed May 22 for the spill zone on the six-day mission. Seven scientists from USF and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commisson's research institute and six crew members are on board.

Video by USF News Intern Amy Mariani.

Underwater Lakes Of Oil From BP Spill Will Continue To Cover Gulf Beaches With Toxic Layer Of Invisible Oil For Months

http://blog.alexanderhiggins.com/2010/07/28/underwater-lakes-of-oil-from-bp-spill-will-continue-to-cover-gulf-beaches-with-toxic-layer-of-invisible-oil-for-months/

As Washington’s Blog reports BP Gulf Oil Spill Clean Up Workers are having a heard time finding crude floating on the surface because BP has used dispersants to sink the oil beneath the surface.

News headlines state that cleanup workers are having a hard time finding oil.

Sounds good, right?

Actually, if BP had let things run their course:

* Oil-skimming vessels could have sucked up most of the oil

* Booms would have stopped most of the oil from hitting the shore

* And oil-eating bacteria would have broken down most of the remaining oil

Instead, BP has used millions of gallons of dispersants to hide the oil by breaking it up, so it sinks beneath the surface.

That means that oil-skimming vessels can’t find it or suck it up.

But as Washington points out that doesn’t mean the oil has magically disappeared as the media is widely reporting.

Experts: Gulf of Mexico Oil is Breaking Up

The light crude began to deteriorate the moment it escaped at high pressure, and then it was zapped with dispersants to speed the process along. The oil that did make it to the ocean’s surface was broken up by 88-degree water, baked by 100-degree sun, eaten by microbes, and whipped apart by wind and waves.

To the contrary has I have pointed out several times as little as 2% of the oil released in the BP Gulf Oil spill may make it to the surface.

The study called Project “Deep Spill” was first a black eye for BP and the Federal Government when they claimed it didn’t make sense that there where huge plumes oil floating in the ambient currents beneath the surface of the sea because as they put it “oil floats”.

Project “Deep Spill” is now hitting them with another black eye and debunks the lie that the methane gas being released from the well is floating to the surface and not being absorbed into the sea.

The study analyzed a wide range of controlled releases at different depths below the sea surface of different types of oil found all over world to help better understand the flow of hydrocarbons released from a deepwater blowout.

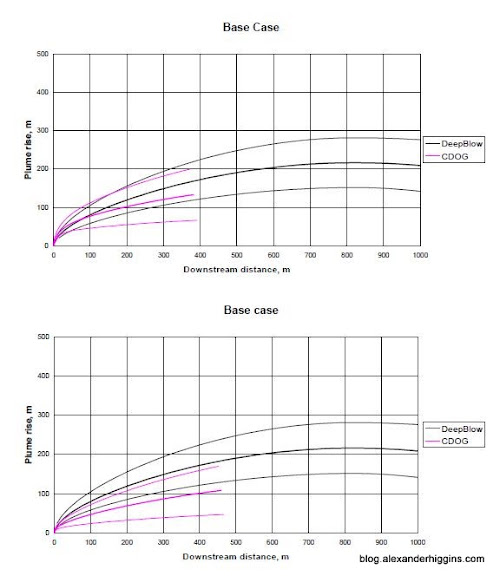

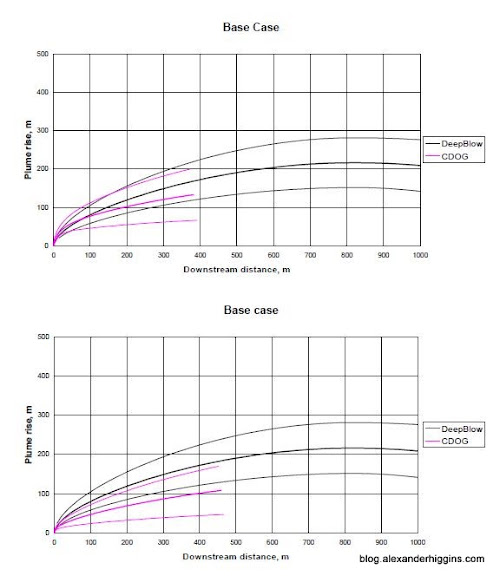

One of the studies, called DeepBlow, released 10,000 barrels of oil per day at a depth of 800 meters which is less than half of the depth of the Deepwater Horizon blowout.

The basic findings of that study has been recreated by scientists from the University of North Carolina.

In their research the scientists simulated of the formation of the underwater oil plumes that are created during deepwater blowouts.

Watch The University of North Caroline Simulation Showing How Oil Released Underwater Forms Plumes

In particular the final report of Project “Deep Spill” found:

- Only 2% of the oil released in a deepwater blowout may actually make it to the surface. That’s as little as 2% naturally without the use of dispersants. Add dispersants into the equation and it could be less then one percent of oil that makes it to the surface.

- None of the methane released from the deepwater blowout made it to the surface. The study found that released natural gas may dissolve completely within the water column if it is released from a deep enough depth relative to the gas flow rate.From the study of the 800 meter release:

Echo sounders provided efficient tracking of oil and gas releases in the field and showed that the gas was completely dissolved before it could surface.

DeepBlow does not include hydrate kinetics, and hence, under hydrate forming conditions, the model predicts solid hydrate particles. Not only is the mass transfer from such particles slower than from gas bubbles, but also hydrate density is closer to that of water than that of natural gas, substantially reducing plume buoyancy.

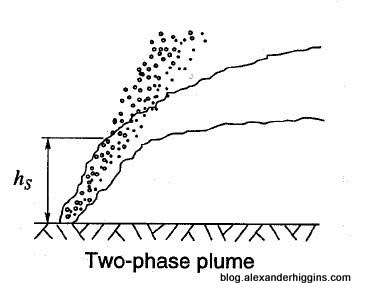

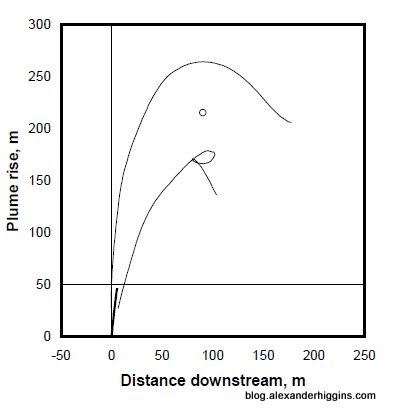

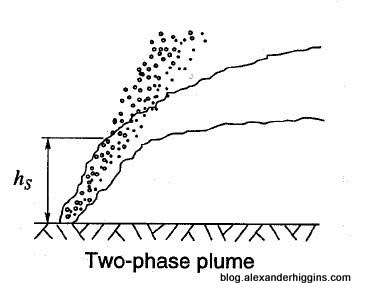

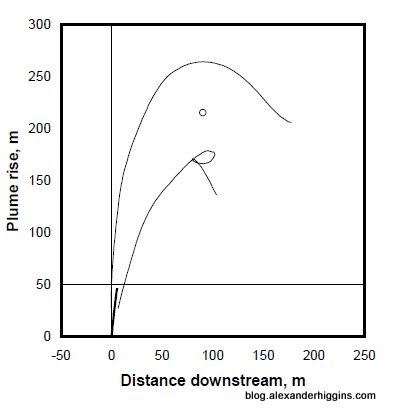

- The buoyant parts of the oil released in a deepwater blowout split from the main plume within the first 200 meters of release. Those buoyant parts, which represent only a small portion of the total amount of oil, turn into small droplets that float to the surface.Here is a graph from the study showing this process.

Deepwater oil release – Buoyancy particle separation graph

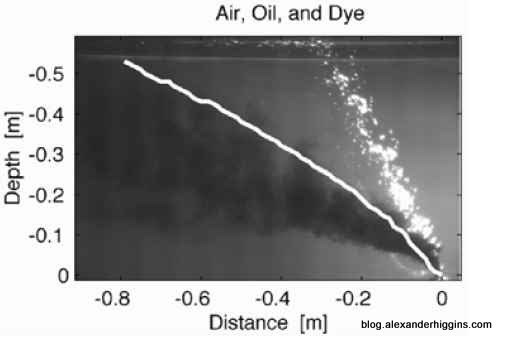

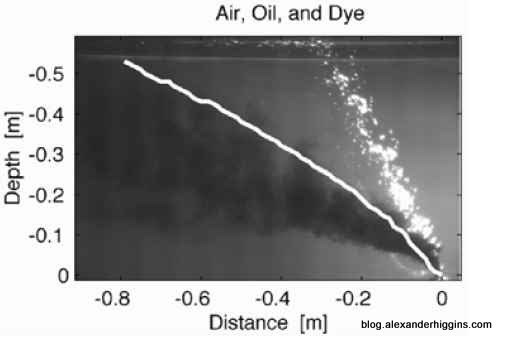

Deepwater oil release – Buoyancy particle separation graphHere is an image that captures the separation process

Deepwater oil release – Buoyancy particle separation simulation

Deepwater oil release – Buoyancy particle separation simulation - Within the first 100 to 200 meters from the source of the release the the majority of the oil loses its buoyancy and stops rising. This majority of the oil remains submerged in an underwater plume that is then carried away by subsurface currents.

Deepwater oil plumes lose buoyancy within the first few couple hundred meters from release

Deepwater oil plumes lose buoyancy within the first few couple hundred meters from release - Oil plumes released from deepwater plumes can travel for long distances. It is uncertain if or where they will surface unless they are tracked.

Deepwater oil plumes travel for long distances

Deepwater oil plumes travel for long distances - A snippet from the study:

Based on the models, the experimental studies described in Section 2 and, to a limited extent, the DeepSpill experiment described in Section 3, an accidental release of oil and/or natural gas obeys the following staged pattern. Near the release, oil, gas and entrained seawater rise as a coherent buoyant plume. A few meters above a point-source release, ambient conditions begin to affect the plume: crossflows cause the plume to deflect in the downstream direction and stratification retards the upward plume motion by entrainment of ambient seawater. For cases similar to the DeepSpill experiment, at a height of order 100 m, these ambient effects arrest the plume, and cause the entrained seawater and the dispersed phases to separate. The arrest takes the form of a completely bent over plume in the case of a strong crossflow, or a trap height and intrusion in the case of a stratification dominated plume. At this terminal level, there is rapid spreading, either by advection from the crossflow or gravitational collapse of the intrusion layer, and the oil is distributed over a wide area. Above this trapping zone, the oil rises as individual droplets.

Recently a NOAA expedition by the Gordon Hunter has confirmed that there are massive underwater lakes of oil floating beneath the surface of the Gulf of Mexico because as a top level whistle blower at the EPA points out the Federal Government has allowed BP to use toxic dispersants to save BP billions in fines.

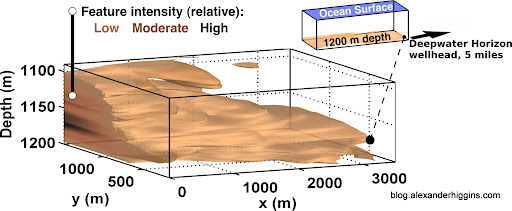

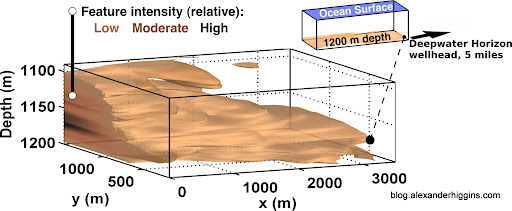

7. Volume visualization

This report summarizes sensor data from AUV surveys conducted on June 2 – 3, when optical and chemical measurements indicated hydrocarbon detection in a plume-like feature below 1000 meters depth. Physical samples were acquired from this feature by ship and AUV sampling systems, and NOAA is managing shore-based laboratory analyses of these samples. When results from these analyses are available, more complete interpretation of the deep feature mapped by the AUV will be possible, including identification of chemical composition, concentration ranges, and source (wellhead or natural seafloor seep).

NOAA Confirms Huge Underwater Lakes Of Oil 1100 Meters Beneath Surface Of Gulf

The illustration above shows the deep plume-like feature mapped by the MBARI AUV Dorado on June 3, 2010. The data and methods used to describe this feature are summarized in this report. The brown hues of the feature represent the tea-like colors of Colored Dissolved Organic Matter (CDOM) because CDOM fluorometry was the basis for feature detection, data analysis and visualization.

As NOAA pointed out in the Brooks McCall report the oil trapped in these underwater lakes of oil will take months to surface.

Review of R/V Brooks McCall Data to Examine Subsurface Oil

Background

This report presents a preliminary analyses of data collected by the R/V Brooks McCall near the site of the Deepwater Horizon MC252 (DWH-MC252) wellhead between May 8 and May 25, 2010. During this timeframe the DWH-MC252 wellhead was releasing gas and oil in a turbulent mixture from the broken riser pipe attached to the well. Throughout the data collection period, a plume of oil and gas continually rose from the wellhead with some oil reaching the surface in about three hours. During the trip to the surface, it is expected that some of the oil dissolved in the water column and some formed droplets. The pressure that propelled the oil out of the wellhead was strong enough to cause some of the oil to form water-in-oil emulsion, or mousse.

Dispersing oil at depth, either naturally or chemically, has the effect of breaking up the oil into small droplets within the water column. Because dispersed oil droplets vary in both size and buoyancy, droplets of different sizes take different lengths of time to rise to the water’s surface. Very small droplets, less than about 100 μm in diameter, rise to the surface so slowly that ocean turbulence is likely strong enough to keep them mixed within the water column for at least several months.

So that means that even though there is no oil visible on the surface of the Gulf layers of toxic oil invisible to the naked eye will continue to wash up on Gulf beaches for months.

In fact an ABC 3 Wear TV Report confirms that while there is no longer visible oil washing up on Pensacola beach an invisible layer of toxic oil from the BP Gulf Oil Spill continues to cover Pensacola Beach.

PENSACOLA BEACH – There appears to be a lot less oil washing up on Pensacola Beach lately. But what about the oil you can’t see?

Dan Thomas joins us now with a Channel Three news investigation.

Retired Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Rip Kirby has spent the last few years studying Northwest Florida beaches.

He’s a Coastal Geologist with the University of South Florida.

When we first met him a few weeks ago, he showed us this… Sheets of oil under the sand, covered by the outgoing tide.

“Buried Tar and it’s constant.”

But lately, less oil has been washing up, and chances are if you dig today, you won’t see it.

Dan Thomas/dthomas@weartv.com: “The Escambia Health Department says if you can see oil, you should avoid contact with it and take a look out here on the Gulf Islands National Seashore there’s really no oil to be seen, that is until you use the UV light. When you shine it on the sand, just like a sheen on the water, it’s there.”

Through the filter of our camera, the sugar white sand becomes blue and what Kirby says is oil, becomes white.

Rip Kirby/USF Coastal Geologist: “So if you just literally, see the oil under neath it.”

Rip Kirby/USF Coastal Geologist: “This is from somebody’s tire track, it just fell off.”

Rip Kirby/USF Coastal Geologist: “The particular oil product that’s in here, was blown there.”

Rip Kirby/USF Coastal Geologist: “This is where people scrape their feet. See all the oil right there?”

The stuff was everywhere, a few inches into the sand, a light dusting on top and still more washing in.

Rip Kirby/USF Coastal Geologist: “There’s no contamination with the white light, only with the UV light. So during the day if some one came out here and sat in the sand, they’re going to get oil product on them just from sitting in the sand. The question becomes how long can they sit in the sand and have it touch their skin and have them lay on the sand with simply a cotton towel between them and this, breathing it before it becomes a toxic problem for them to deal with 20 years from now when they have some kind of cancer? The answer to that is, I don’t know.”

Rip Kirby/USF Coastal Geologist: “We haven’t seen and I’ve been looking for it for six weeks now and I have not seen a report that tells me the chemical constituents of the oil product that’s in the beach sand.”

We put a call in to BP… They say they’re working on getting us that report.

So far we haven’t seen it either.